How your innocent smartphone passes on almost your entire life to the secret service

Intelligence services collect metadata on the communication of all citizens. Politicians would have us believe that this data doesn’t say all that much. A reader of De Correspondent put this to the test and demonstrated otherwise: metadata reveals a lot more about your life than you think.

This article was originally written in Dutch by Dimitri Tokmetzis and was published by De Correspondent. Illustrations by Momkai.

Ton Siedsma is nervous. He made the decision weeks ago, but keeps postponing it. It’s the 11th of November, a cold autumn evening. At ten past eight (20:10:48 to be exact), while passing Elst station on the way home, he activates the app. It will track all of his phone’s metadata over the coming week.

Metadata is not the actual content of the communication, but the data about the communication; like the numbers he calls or whatsapps, and where his phone is at a particular moment. Whom he e-mails, the subject of the e-mails and the websites he visits.

Ton won’t be doing anything out of the ordinary. He’ll just lead his normal life. On weekdays, this means biking from his house in Nijmegen to the station and taking the train to Amsterdam. On Saturday, he’ll drive his car to Den Bosch and spend the night near Zuiderpark, returning to Nijmegen the next day by public transportation. Later on in the day he’ll have some drinks at a café called St. Anna.

After exactly a week, on Monday, 18 November, he concludes the experiment, saying afterwards that he felt liberated when doing so. There’s an easy explanation for his nervousness: what he’ll be doing, where he’ll be and who he has contact with will be seen by tens of thousands of people. Today, by you and me, and all the other readers of this article.

Over the past months, it’s become clear that intelligence agencies, spearheaded by the National Security Agency (NSA), are collecting enormous amounts of metadata. This includes recording e-mail traffic and location data from mobile phones. From the outset, politicians and intelligence agencies have defended this surveillance by emphasising that the content of the communication is not being monitored, the idea being that the agencies are only interested in metadata. According to President Obama and the NSA, as well as the Dutch Minister of the Interior, Ronald Plasterk, and the Dutch Intelligence Agency (AIVD), there isn’t much harm in it. Even recently, on its website, the AIVD described the interception of metadata as ‘a minor infringement of privacy’.

But is that the case? Certainly not, as Ton Siedsma’s experiment demonstrates. Metadata - including your metadata - reveals more than you think, and much more than the authorities would have you believe.

One week says enough

I submitted Ton’s metadata to the iMinds research team of Ghent University and Mike Moolenaar, owner of Risk and Security Experts. I also ran my own analysis. From one week of logs, we were able to attach a timestamp to 15,000 records. Each time Ton’s phone made a connection with a communications tower and each time he sent an e-mail or visited a website, we could see when this occurred and where he was at that moment, down to a few metres. We were able to infer a social network based on his phone and e-mail traffic. Using his browser data, we were able to see the sites he visited and the searches he made. And we could see the subject, sender and recipient of every one of his e-mails.

This chart displays Ton’s daily routine of using e-mail, the Internet and his phone. We can see, for instance, that he whatsapps a lot each day at around two o’clock, right after lunch.

So, what did we find out about Ton?

This is what we were able to find out from just one week of metadata from Ton Siedsma’s life. Ton is a recent graduate in his early twenties. He receives e-mails about student housing and part-time jobs, which can be concluded from the subject lines and the senders. He works long hours, in part because of his lengthy train commute. He often doesn’t get home until eight o’clock in the evening. Once home, he continues to work until late.

His girlfriend’s name is Merel. It cannot be said for sure whether the two live together. They send each other an average of a hundred WhatsApp messages a day, mostly when Ton is away from home. Before he gets on the train at Amsterdam Central Station, Merel gives him a call. Ton has a sister named Annemieke. She is still a student: one of her e-mails is about her thesis, judging by the subject line. He celebrated Sinterklaas this year and drew lots for giving gifts.

Ton likes to read sports news on nu.nl, nrc.nl and vk.nl. His main interest is cycling, which he also does himself. He also reads Scandinavian thrillers, or at least that’s what he searches for on Google and Yahoo. Other interests of his are philosophy and religion. We suspect that Ton is Christian. He searches for information about religion expert Karen Armstrong, the Gospel of Thomas, ‘the Messiah book Middle Ages’ and symbolism in churches and cathedrals. He gets a lot of information from Wikipedia.

Ton also has a lighter side. He watches YouTube videos like ‘Jerry Seinfeld: Sweatpants’ and Rick Astley’s Never Gonna Give You Up. He also watches a video by Roy Donders, a Dutch reality TV sensation. On the Internet, he reads about ‘cats wearing tights’, ‘Disney princesses with beards’ and ‘guitars replaced by dogs’. He also searches for a snuggie, with a certain ‘Batman Lounger Blanket With Sleeves’ catching his eye. Oh, and he’s intensively looking for a good headset (with Bluetooth, if possible).

If we were to view Ton’s profile through a commercial lens, we would bombard him with online offers. He’s signed up for a large number of newsletters from companies like Groupon, WE Fashion and various computer stores. He apparently does a lot of shopping online and doesn’t see the need to unsubscribe from the newsletters. That could be an indication that he’s open to considering online offers.

He keeps his e-mail communication reasonably well separated, using three different e-mail accounts. He receives all promotional offers on his Hotmail account, which he also uses to communicate with a number of acquaintances, though he hardly sends any messages himself from the account. He has a second personal e-mail account, which he uses for both work and correspondence with closer friends. He uses this account much more actively. Lastly, he has an e-mail account for work.

Ton knows a lot about technology. He’s interested in IT, information security, privacy issues and Internet freedom. He frequently sends messages using encryption software PGP. He performs searches for database software (SQLite). He is a regular on tech forums and seeks out information about data registration and processing. He also keeps up with news about hacking and rounded-up child pornography rings.

We also suspect that he sympathises with the Dutch ‘Green Left’ political party. Through his work (more about that later), he’s in regular contact with political parties. Green Left is the only party from which he receives e-mails through his Hotmail account. He has had this account longer than his work account.

A day in the life of Ton Siedsma: Tuesday 12 November 2013. On this day, he takes a different route home from Amsterdam to Nijmegen than his usual route via Utrecht. He receives a phone call from Hilversum and drops by the Mediapark on his way home.

What kind of work does Ton do?

Based on the data, it is quite clear that Ton works as a lawyer for the digital rights organisation Bits of Freedom. He deals mainly with international trade agreements, and maintains contact with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a few Members of Parliament about this issue. He follows the decision-making of the European Union closely. He is also interested in the methods of investigation employed by police and intelligence agencies. This also explains his interest in news reports about hacking and rounded-up child pornography rings.

During the week under analysis, Ton takes active part in an e-mail discussion with colleagues on the topic of ‘Van Delden must go’. The e-mails pertain to Bert van Delden, the chairman of the Intelligence and Security Services Review Committee (CTIVD), which is the supervisory body for intelligence agencies AIVD and MIVD. Ot van Daalen, a colleague, has also been working during the week to devise a strategy for the ‘Freedom Act’, which is apparently a Bits of Freedom project.

On Thursday, Ton sends a message to all employees entitled ‘We’re in the clear!’ There is apparently a reason for relief. Ton also takes a look at a thesis on stealth SMS, and it’s determined who will go to a panel discussion of the Young Democrats. A number of messages are about scheduling a performance review, which will probably be administered by Hans, the director of Bits of Freedom.

Ton updates a few files for himself on a restricted section of the Bits of Freedom website. We can retrieve the names of the files from the URLs he uses. They deal with international trade agreements, the Dutch parliament, WCIII (Computer Crime Act III) and legislation. Ton also updates the website. It’s easy for us to see which blog articles he has revised.

In his free time, Ton doesn’t appear to do all that much. He continues to send and receive work e-mails until late into the evening. Ton also browses a lot of news sites and whatsapps individuals who are unknown to us. He usually goes to bed around midnight.

Who does Ton interact with?

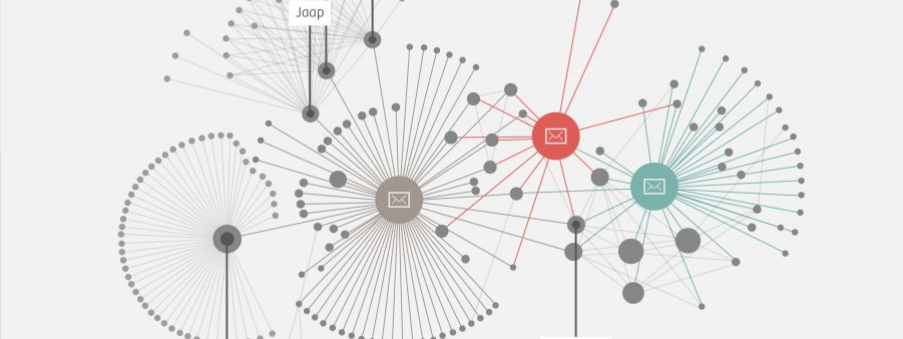

The social network of Ton Siedsma (based on his e-mail behaviour) reveals different clusters.

From a social network analysis based on Ton’s e-mail traffic, it is possible for us to discern different groups to which he belongs. These clusters are formed by his three e-mail accounts. It may be the case that the groups would look a bit different if we were also to use the metadata from his phone. However, we agreed to not perform any additional investigation, such as actively attempting to discover the identity of the user of a particular number, so as to protect the privacy of those in Ton’s network.

Through his Hotmail account, Ton communicates with friends and acquaintances. Thomas, Thijs and Jaap appear to be the main contributors in a larger group of friends. Judging by their e-mail addresses, this group consists only of men. There is also a line of communication with a separate group headed by someone named ‘Bert’. The nature of this group is the only thing that was censured by Ton. He says that it is simply a personal matter.

The social network of Ton Siedsma based on his personal e-mail.

We can make out another, smaller group of friends, namely Ton, Huru, Tvanel and Henry. We think that they are friends because they all participate in the e-mail discussion, i.e. they know each other. What’s more, a number of them also send e-mails to ton@sieds.com, Ton’s address for friends and family.

Lastly, there is also Ton’s work cluster. We see here that his primary contacts are Rejo, Hans and Tim. Tim and Janneke are the only ones who also show up in his personal e-mail correspondence. The number of e-mails sent between him and his six colleagues is strikingly large. There’s apparently a cc-ing culture at Bits of Freedom. It’s rare for Ton to e-mail just one colleague, but when that happens it’s mostly either Rejo or Tim. A lot of e-mails are sent to the group address for all employees.

The social network of Ton Siedsma based on his work e-mail.

Ton has relatively little contact with external parties. During the week, he sends the necessary e-mails to set up an appointment with the assistant to Foort van Oosten, a member of parliament from the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), and a journalist by the name of Bart. He also corresponds a lot with providers of anti-virus software.

Based on the metadata, security expert Mike Moolenaar concludes that Ton has ‘a good information position within Bits of Freedom.’ He appears to have a good idea of what is going on – an important fact when looking at this network from an intelligence perspective.

But that’s not all. The analysts from the Belgian iMinds compared Ton’s data with a file containing leaked passwords. In early November, Adobe (the company behind the Acrobat PDF reader, Photoshop and Flash Player) announced that a file containing 150 million user names and passwords had been hacked. While the passwords were encrypted, the password hints were not. The analysts could see that some users had the same password as Ton, and their password hints were known to be ‘punk metal’, ‘astrolux’ and ‘another day in paradise’. ‘This quickly led us to Ton Siedsma’s favourite band, Strung Out, and the password “strungout”,’ the analysts write.

With this password, they were able to access Ton’s Twitter, Google and Amazon accounts. The analysts provided a screenshot of the direct messages on Twitter which are normally protected, meaning that they could see with whom Ton communicated in confidence. They also showed a few settings of his Google account. And they could order items using Ton’s Amazon account - something which they didn’t actually do. The analysts simply wanted to show how easy it is to access highly sensitive data with just a little information.

What they and I have done for this article is child’s play compared with what intelligence agencies could do. We focused primarily on metadata, which we analysed using common software. We refrained from undertaking additional investigation, with the exception of using the leaked dataset from Adobe.

Moreover, this experiment was limited to a week. An intelligence agency has metadata on many more people over a much longer period of time, with much more advanced analysis tools at its disposal. Internet providers and telecommunications companies are required by law in the Netherlands to store metadata for at least six months. Police and intelligence agencies have no difficulty asking for and receiving this kind of data.

So the next time you hear a minister, security expert or information officer say ‘Oh, but that’s only metadata,’ think of Ton Siedsma - the guy you now know so much about because he shared just a week of metadata with us.